The NCCPA™ Gastroenterology and Nutrition PANCE Content Blueprint covers three topics under the category of gastric disorders

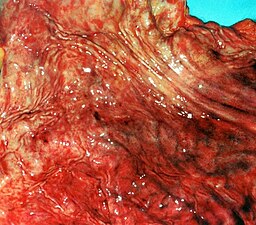

| Gastritis | Patient will present as → a 37-year-old male with a history of daily NSAID use complaining of epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting, all worsened by eating. On physical examination, he is tender to palpation in the epigastrium. He admits to drinking approximately two beers per day. Dyspepsia (belching, bloating, distension, and heartburn) and abdominal pain are common indicators of gastritis Three causes: 1. Infection - H. pylori (most common)

2. Inflammation of the stomach lining (NSAIDS and Alcohol)

3. Autoimmune or hypersensitivity reaction (e.g., pernicious anemia)

Treatment and diagnosis: stop NSAIDs, empiric therapy with acid suppression 4-8 wks. of PPI

|

| Gastroparesis | Patient will present as → a 32-year-old female with a longstanding history of type 1 diabetes presents with chronic nausea, early satiety, bloating, and significant weight loss over the past six months. She reports that her symptoms are particularly worse after eating. Despite maintaining strict control of her blood sugar levels, she experiences these gastrointestinal symptoms frequently. On examination, she appears malnourished and mildly dehydrated. Abdominal examination reveals a mildly distended abdomen with minimal tenderness. A gastric emptying study is performed, showing delayed gastric emptying without any obstruction. Based on these findings, she is diagnosed with diabetic gastroparesis. Dietary modifications are initiated, and she is started on metoclopramide to facilitate gastric motility, with close monitoring for potential side effects. Gastroparesis, also called delayed gastric emptying, is a disorder that slows or stops the movement of food from the stomach to the small intestine in the absence of mechanical obstruction

DX: Gastric Emptying Study (scintigraphy) is the gold standard for diagnosis

TX: Dietary modification is considered first-line therapy in patients with mild gastroparesis

|

| Peptic ulcer disease | Gastric ulcer: Patient will present with → abdominal discomfort that is worse with meals and gets better an hour or so later after eating.

Duodenal ulcer: Patient will present as → a 62-year-old female with complaints of epigastric pain and belching, which improves when she eats food but gets worse a few hours after her meal. She said he has noticed a change in the color of her stool. PUD is an ulcer of the upper GI tract mucosa involving the proximal duodenum (90%) and distal stomach (10%). There are 2 main types of ulcers: duodenal and gastric Duodenal ulcer (food classically decreases pain - think Duodenum = Decreased pain with food)

Gastric ulcer (food classically causes pain)

Bleeding — Acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage is the most common complication of peptic ulcer disease DX: Upper endoscopy is the most accurate diagnostic test for peptic ulcer disease

TX: All patients with peptic ulcers should receive antisecretory therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) (eg, omeprazole 20 to 40 mg daily or equivalent) for 4-8 weeks

|

| Pyloric stenosis | ReelDx Virtual Rounds (Pyloric stenosis)Patient will present as → a 3-week-old male infant with frequent projectile vomiting after feeding, increasing in frequency and intensity over the past week. He appears dehydrated with decreased skin turgor, and examination reveals a palpable olive-shaped mass in the right upper quadrant and visible peristaltic waves. Laboratory tests show hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. On a barium upper GI series report, the radiologist states a “string sign” is present. An abdominal ultrasound confirms hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. After fluid and electrolyte repletion, the infant successfully undergoes pyloromyotomy, resulting in the resolution of vomiting and improved feeding tolerance. Pyloric stenosis is a congenital condition where a newborn’s pylorus undergoes hyperplasia and hypertrophy, leading to obstruction of the pyloric valve which causes vomiting (that might be projectile), as well as dehydration and metabolic alkalosis Projectile vomiting occurs shortly after feeding in an infant < 3 mo. old with a palpable “olive-like” mass at the lateral edge of the right upper quadrant

DX: Diagnosis is by ultrasound

TX: surgical correction - pyloromyotomy (Ramstedt's procedure) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | Patient will present as → a 50-year-old male with a history of alcohol use and NSAID use for chronic knee pain. He presents with melena for the past two days and a feeling of lightheadedness upon standing. He denies any vomiting, but notes a recent decrease in appetite and weight loss. On examination, he is pale, with a heart rate of 110 bpm and blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg. Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding can be classified as upper or lower, depending on the location of the bleeding source. It can present as hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia, depending on the location and rate of bleeding

DX:

TX:

|

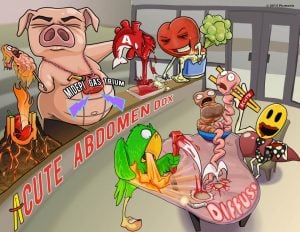

| Acute abdomen is a general term used to describe any patient condition that involves sudden onset and severe abdominal pain. There are many conditions that may or may not require emergent surgery to treat, which is why it is important to be able to quickly identify the cause. It can be helpful to sort the causes of acute abdomen into the classically defined region of abdominal pain. Pain can manifest in any location in cases of bowel obstruction, peritonitis, mesenteric ischemia, and strangulation. | |

|

The causes within the right upper quadrant (RUQ) include cholecystitis, biliary colic, cholangitis, perforated duodenal ulcer, and acute hepatitis. The causes within the left upper quadrant (LUQ) include splenic rupture and irritable bowel syndrome in conjunction with splenic flexure syndrome. |

> |

Midepigastric pain can be due to pancreatitis, aortic dissection, peptic ulcer disease, and myocardial infarction. |

|

Causes within the lower quadrants include ovarian torsion, ectopic pregnancy, pyelonephritis, renal calculi, and acute salpingitis. Appendicitis is most commonly associated with right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain, and causes within the left lower quadrant (LLQ) include sigmoid volvulus and sigmoid diverticulitis. |

Picmonic

Picmonic