Patient will present as → a 1-year-old female with a temperature of 103.1 and irritability. A culture of a urine specimen is obtained and shows more than 106 colony-forming units of pansensitive Escherichia coli per milliliter. She is treated with intravenous ampicillin for several days, followed by oral ampicillin, for a total of 14 days of therapy. After the patient no longer had a fever and a urine culture was sterile, voiding cystourethrography was performed while the patient was still receiving ampicillin. The voiding cystourethrogram demonstrates bilateral grade III vesicoureteral reflux, and renal ultrasonography revealed normal findings.

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a condition in which urine flows retrograde, or backward, from the bladder into the ureters/kidneys

There are two types of vesicoureteral reflux

- Primary vesicoureteral reflux is the most common type and happens when a child is born with a defect at the ureterovesical junction

- In secondary vesicoureteral reflux, there’s an obstruction at some point in the urinary tract that causes an increase in pressure, causing urine to flow backward into the ureters or kidneys

- Secondary vesicoureteral reflux is most commonly caused by recurrent urinary tract infections

- Other causes include posterior urethral valve disorder, an neurogenic bladder

- In young female patients, any history that points to recurrent infection, especially cystitis or pyelonephritis, should trigger an evaluation for vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)

Diagnose by using voiding cystourethrography (VCUG)

- Monitor by using serial ultrasonography and VCUGs

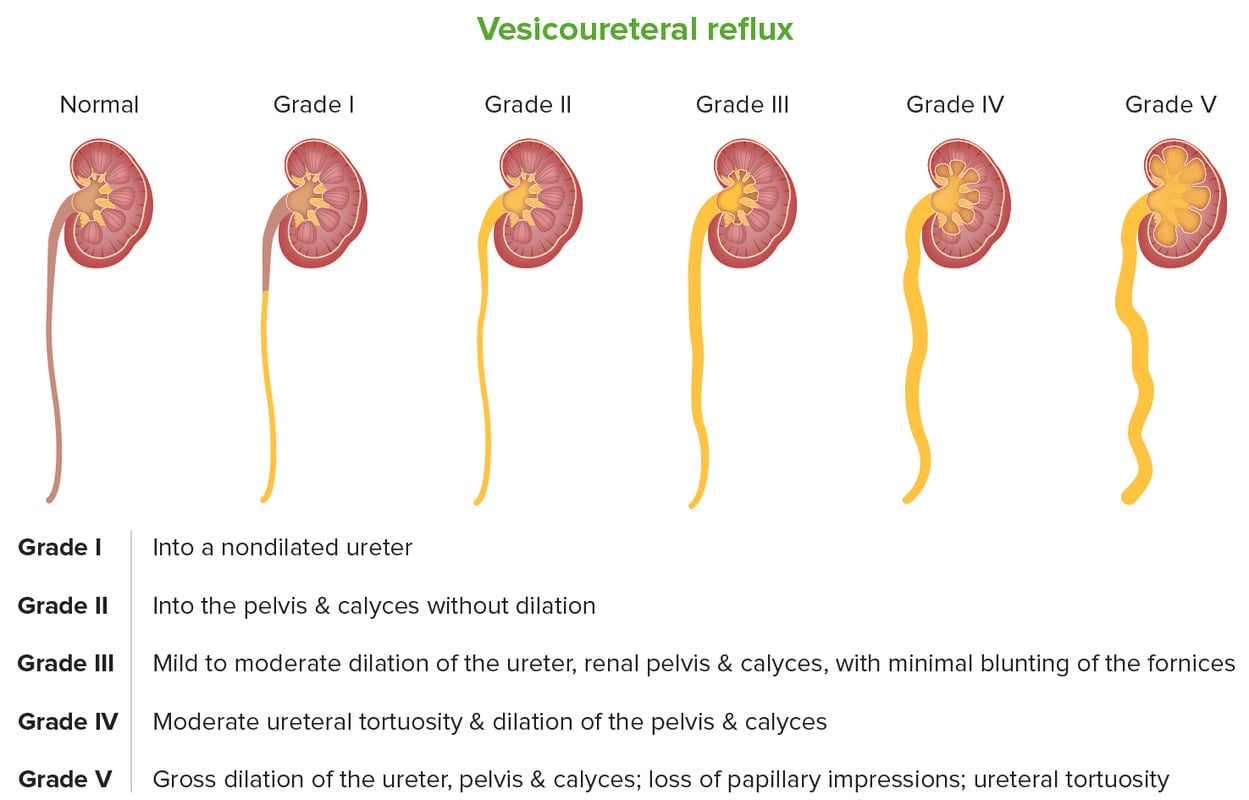

Vesicoureteral reflux is usually classified by severity ⇒ how far urine refluxes back up into the urinary tract

- Grade I – reflux into non-dilated ureter

- Grade II – reflux into the renal pelvis and calyces without dilatation

- Grade III – mild/moderate dilatation of the ureter, renal pelvis, and calyces with minimal blunting of the fornices

- Grade IV – dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces with moderate ureteral tortuosity

- Grade V – gross dilatation of the ureter, pelvis, and calyces; ureteral tortuosity; loss of papillary impressions

Mild to moderate VUR often resolves spontaneously, but the more serious disease may require surgical intervention

- Children with newly diagnosed VUR are given prophylactic antibiotics depending on their clinical course

- Antibiotics are administered nightly at half the normal therapeutic dose

Question 1 |

Dark-colored urine Hint: Dark-colored urine and painless hematuria are concerning history findings, but point more toward a renal cause of disease. | |

Epigastric abdominal pain Hint: Epigastric abdominal pain is not seen in patients with VUR and any pain associated with VUR, if present, would most likely be located in the renal or suprapubic areas. | |

Nocturnal enuresis Hint: Although incontinence can be a sign of cystitis, enuresis limited to night would likely not be present in the presence of infection. | |

Painless hematuria Hint: Dark-colored urine and painless hematuria are concerning history findings, but point more toward a renal cause of disease. | |

Recurrent cystitis |

Question 2 |

Continue current antibiotic prophylaxis regimen Hint: Continuing the ineffective antibiotic prophylaxis would not address the breakthrough infection or high-grade reflux. | |

Obtain DMSA (dimercapto succinic acid) renal scan Hint: A DMSA renal scan could evaluate for new scarring but does not address definitive correction of reflux. | |

Start cephalexin for UTI treatment Hint: Cephalexin would treat the acute UTI but does not correct the underlying reflux. | |

Consider surgical correction | |

Stop antibiotic prophylaxis Hint: Stopping antibiotic prophylaxis is not appropriate given his high-grade reflux and recurrent infections. |

|

List |

References: Merck Manual · UpToDate

Osmosis

Osmosis